Aleppo – Aleppo Citadel حلب – قلعة حلب

One of the most incredible fortifications in Syria, and the whole of the Middle East, is the magnificent Aleppo Citadel (قلعة حلب). Located on a naturally formed hill at the center of the old city, the site has been in use since at least the 3rd millennium BCE. It was referenced in cuneiform tablets from Ebla (ايبلا) and Mari (ماري), and a recently excavated temple dedicated to Hadad dates to the 24th century BCE. The hill was used for defensive purposes as far back as the 16th century BCE, when the Hittites conquered the city from the Amorites.

The Seleucids constructed fortifications at the site, which they held between 333 and 64 BCE. There are few remains and little documentation about the site from the Roman period, though Emperor Julian is known to have visited the fortress in 363 CE. During the Byzantine period the fortress is known to have served the city’s defenses against Sasanian Persian attacks, though few Byzantine remains are evident. The importance of Aleppo (حلب) declined significantly in the period following the Arab conquest, and the state of the citadel during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods is largely unknown.

Aleppo (حلب) started to regain its significance in the 10th century under the Hamdanid dynasty and in the 11th century under the Mirdasid dynasty. During that time, two churches of the fortress were converted to mosques. The city defenses were rebuilt during the 12th century reign of Nur al-Din Mahmoud Zenki (نور الدين محمود زنكي), including reinforcements to the Aleppo Citadel (قلعة حلب). Most of what survives today, however, is based on a major reconstruction of the castle undertaken under al-Zahar Ghazi Bin Salah al-Din al-Ayoubi (الظاهر غازي بن صلاح الدين الايوبي), the Ayyubid ruler of Aleppo (حلب) and Mosul (Iraq) from 1186 until 1216. In addition to defensive improvements, a large palace, baths and other buildings were constructed. Born in 1172, al-Zahar Ghazi (الظاهر غازي) was the third son of Salah al-Din Yousef Bin Ayoub (صلاح الدين يوسف بن أيوب). He was given control of this northern area of the Ayyubid empire at the young age of fifteen, while his two older brothers divided rule over the southern parts of their father’s empire. al-Zahar Ghazi (الظاهر غازي) passed away in 1216, and is buried in the neighboring al-Sultaniyeh Mosque (جامع السلطانية).

The citadel was heavily damaged when the Mongols attacked Aleppo (حلب) in 1260. It was restored in 1292. Further destruction was inflicted upon the citadel in 1400, when the city was conquered by Timur. Mamluk governor Seif al-Din Jakam (سيف الدين جكم) had the citadel rebuilt in 1415, adding the two external towers on the north and south slopes of hill, and constructing a new palace above the two main entrance towers. The enormous throne hall of the Mamluk palace had nine domes added to its ceiling under al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri (الأشرف قانصوه الغوري) in the early 1500s. During the Ottoman period the citadel saw periodic military occupation, but was mostly inhabited by civilians. It was restored under Ottoman Sultan Suleiman in 1521, then again in 1850-1851 to repair damage from a 1822 earthquake.

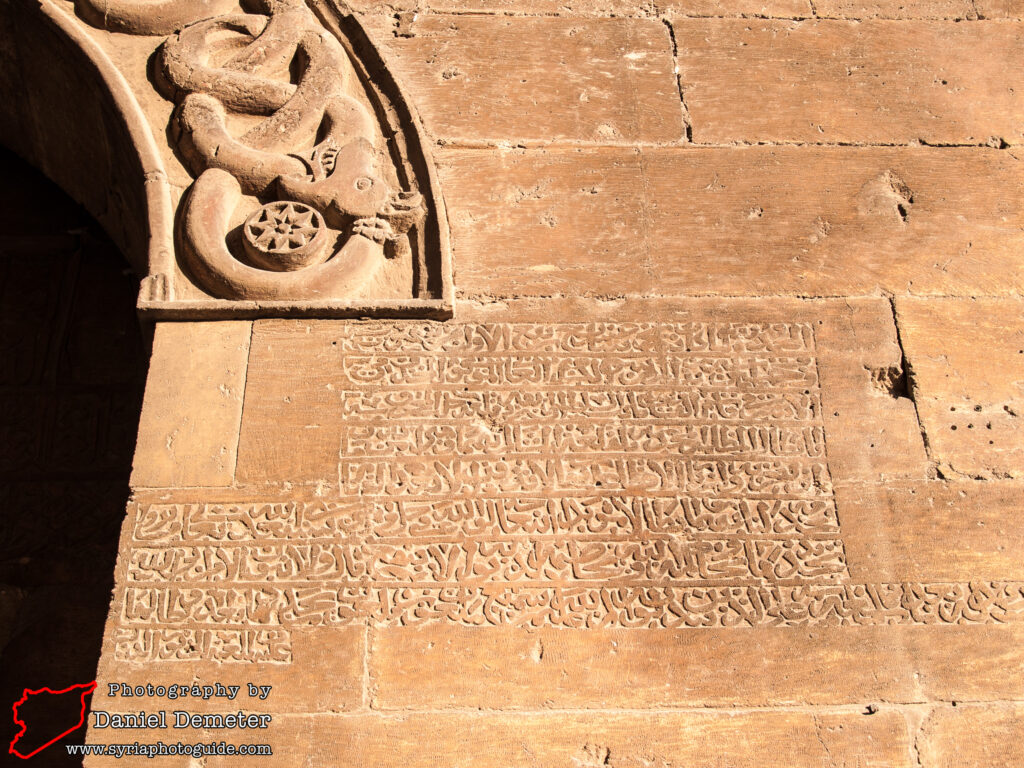

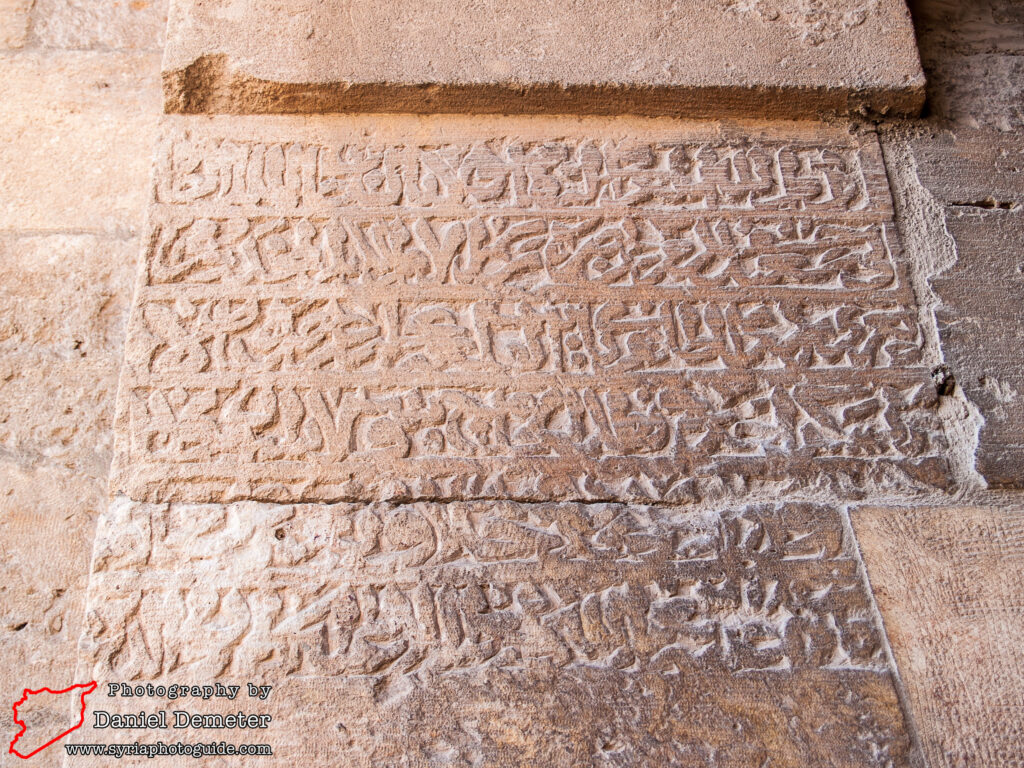

Visitors enter the castle by crossing a massive stone bridge, supported by eight arches, over the surrounding moat. Preceding the bridge is a small entrance tower, dating to the reign of al-Zahar Ghazi (الظاهر غازي) and rebuilt under al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri (الأشرف قانصوه الغوري). The bridge leads to a massive gateway, arguably the most remarkable of any fortification in the Arab world. Originally two separate towers, these were combined into a single monumental gateway during the reconstruction undertaken by Seif al-Din Jakam (سيف الدين جكم) in 1415. Inscriptions surrounding the entrance refer to earlier restorations to these towers, performed under al-Ashraf Salah al-Din Khalil Bin Qalawoun (الأشرف صلاح الدين خليل بن قلاوون) between 1290-1293. The entryway to the castle features eight ninety-degree turns and is heavily exposed to defensive positions overhead, making any assault on the main gateway exceptionally difficult. At the far end of the gateway, stairways lead down to a series of cisterns and dungeons, possibly of Byzantine origin. This may have been where Crusader leaders captured in battle were imprisoned.

After passing through the gateway, a path leads into the open interior of the citadel. Ruins of the Ayyubid palace can be found on the right, the remains largely dating from a 1230 reconstruction under al-Aziz Mohammed (العزيز محمد). The entrance façade is particularly remarkable, with alternating black basalt and yellow limestone and excellent muqarnas work. The palace was constructed around a large central courtyard with four iwans. There is a private hammam (baths) attached. Northwest of the palace complex are two mosques. The smaller, southern mosque is attributed by inscription to the rule of Nur al-Din (نور الدين). Known as Ibrahim Mosque (مسجد إبراهيم), local tradition holds that a stone on which Abraham used to sit was preserved on the site, previously commemorated by a church. The mosque is also one of several sites said to contain the burial place of the head of John the Baptist. Further north is the Great Mosque of the Aleppo Citadel (الجامع الكبير في قلعة حلب), constructed from the remains of a church under the Mirdasids. The square plan features a central courtyard with prayer hall to the south. The minaret, to the north, dates to the same period. Neighboring the mosque is an Ottoman-era barracks built in 1834, now a museum and visitor’s center. When returning to the main entrance, ascend to the terrace at the rear of the gateway. This leads to the Mamluk-era palace built during the reign of Seif al-Din Jakam (سيف الدين جكم)in 1415. The remarkable throne hall, approached through a courtyard decorated with black and white stone and muqarnas, measures an impressive twenty-four meters by twenty-seven meters. It represents a rare example of a Mamluk reception hall.

The Aleppo Citadel (قلعة حلب), currently held by Syrian government forces, has been seriously damaged during ongoing fighting in the city since 2012. While much of the damage has been cosmetic rather than structural, the citadel remains under constant threat of being destroyed by the same tunnel bombs that have demolished surrounding historic buildings. Rocket propelled grenades have struck inside of the castle, causing unknown damage to internal structures.

Getting There: The Aleppo Citadel (قلعة حلب) is difficult to miss, towering above the old city of Aleppo (حلب). The markets (اسواق) of the old city extend to the west of the castle, where the Great Mosque of Aleppo (جامع حلب الكبير) is also located.

Coordinates: 36°11’57.00″N / 37°09’46.00″E

Transliteration Variants: Qalaat Halab, Qalaat Haleb

Rating: 10 / 10